The Smuggler’s Stone: Whisky, Violence, and Justice in 19th-Century Maryhill

Words by William B. Black

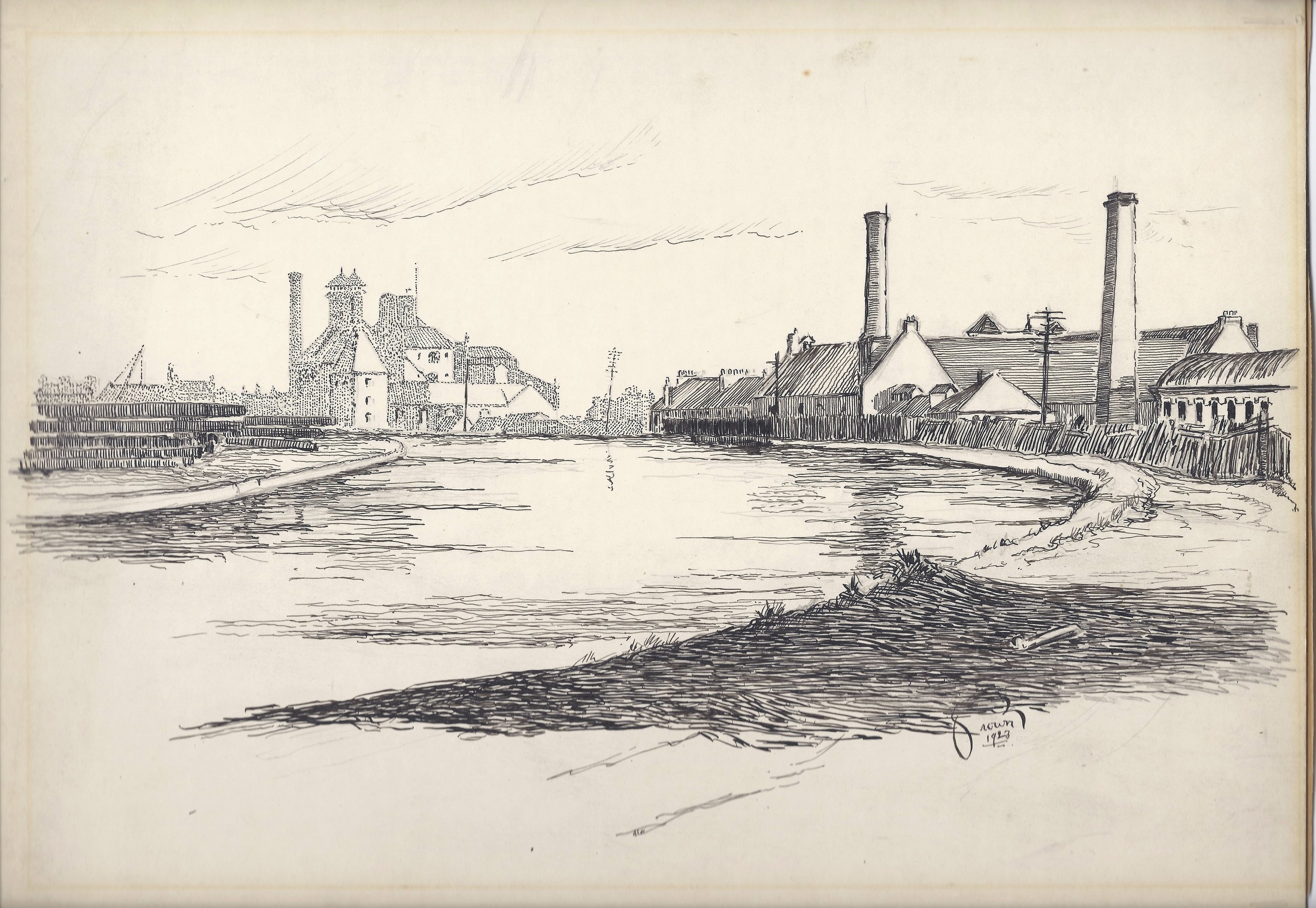

Sketch of the canal between the Old Basin and Firhill Basin, 1920 - Maryhill Burgh Halls Collection

In his memoir of Maryhill, Random Notes & Rambling Recollections, Alexander Thomson mentions the

‘Smuggler’s Stone.’ Apparently it stood on the canal side of Maryhill Road, almost opposite Braeside Street, but was lost to view when the canal company erected a fence around 1870. As no trace remains today it must have been removed around the same time.

At the beginning of the 19th century, whisky smuggling was an expanding business in the West of Scotland, partly due to the high rate of duty imposed on the lowland districts. The produce of illicit stills along the margins of the highlands found a ready market in the Glasgow area and the toll road from Drymen, which ran through Maryhill was a route used frequently by the smugglers. Among those was a gang known to be operating from Aberfoyle, including in its number Duncan McFarlane, the carrier from Gartmore. At the beginning of April 1813, James Anderson, a customs supervisor, had intercepted eight of them at Canniesburn Toll, all of whom were seen to have tin containers strapped to their backs. It was known that this was the normal mode of transport and that each container could carry five gallons of spirit, around twenty-three litres. Unfortunately the gang was on the return journey to Aberfoyle and the containers were empty, preventing the excise officers from taking action. However, as the smugglers passed, they showed that they were armed with stout cudgels (a short, thick stick used as a weapon) and made serious threats at the excise men. That this was no idle threat had been shown on 16th March after excise officers captured whisky near Bishopbriggs. As they returned to their base at Port Dundas they were attacked by four armed men, who recovered the whisky. In this attack, one of the customs officers, Quintin Dick, had been stabbed three times.

During the month, intelligence was received that the Aberfoyle gang were to make another run and plans were made to ambush them. After dark, on Thursday 29th April, eight excise officers left Port Dundas, including Dick, who had recovered from his wounds sufficiently to be on duty. All of this party was armed, at least two carrying stuff sticks, stout wooden sticks within which was concealed a removable spike with a sharpened tip. Officially, they were used to probe suspicious parcels but would provide a useful defence against armed smugglers. In addition, three of the party carried pistols, although the usual customs weapon, the cutlass (a short sabre), was not provided, although this was usual when armed resistance was expected.

It was known that many in the local population were sympathetic to the smugglers, so to avoid detection they came along the canal towpath until they had passed Firhill Bridge. As the canal continued towards Ruchill Bridge it came within 30 ft (9 metres) of the Toll Rd (Maryhill Road), where it was about 10.5 ft (3.5 m) lower than the towpath. On the opposite side of the road, the ground rose steeply on a hill known as Sheepmount to a height of 41 ft (12.5 m) above the road, with no other obvious escape route. Today this ambush point is above Braeside Street, where the road curves towards Kelvinside Avenue. In 1813, there were no houses on this stretch, the closest being the lodge for Kelvinside Estate, which stood at the top of what became Kelvinside Avenue, while on the opposite side of the road was Kelvinside Cottage.

Ambush site - from NB 1859 OS Map, most houses shown did not exist in 1813

The ambush party was on site just after Midnight, concealing themselves on the Sheepmount side of the road and, after an hour and twenty minutes, they heard a party of people coming from the Maryhill direction.

The night was very dark and the smuggling party spread out, probably as a precaution against all being caught by an ambush. As the first group passed, the excise officers jumped out onto the road and ordered them to drop their burdens but, in the excitement, failed to identify themselves as excise officers. However, later, most of the smugglers, of whom there were eight, admitted that they did not doubt the identity of their assailants. In the initial attack, the unfortunate Dick was struck on the head by a cudgel and fell to the ground dazed. Initially, the excise officers were able to push the smugglers across the road but, as the fight developed, they were forced to retreat back to the Sheepmount side.

At one point, another of the excise officers William McDowall, was struck on the head by a cudgel and fell to the ground. Although he suffered a serious cut, he was wearing both a hat and a nightcap, this improvised protection saving him from ore serious injury or death. Suddenly, a shot rang out and one of the smugglers, Malcolm McGregor, shouted out to McFarlane, who was near him ‘Duncan! I’m gone!’ Unlike the other smugglers, McGregor was a labourer from Anderston but may have had relations in the Aberfoyle area. He had been struck in the left thigh and McFarlane pulled him over the wall bordering the road and into the trees, to conceal the wounded man from their opponents. Another of the smugglers, Peter McAlpine, had been knocked into the roadside ditch during the initial scuffle and, as he lay there, the excise officers rallied once more, forcing the remaining smugglers to flee back towards Maryhill.

Other than the officers mentioned, Nathaniel Ingram, Campbell Gardner and Neil Buchanan had also received injuries during the fight, but none was serious. Although they had driven off the smugglers, past experience suggested they might return with reinforcements, so the priority was to confiscate the whisky. By the time the officers began to gather the flasks, McFarlane and McAlpine had emerged from hiding and managed to recover two of them before following their companions away from the scene. Thus six flasks were picked up by the excise officers, who returned to Port Dundas once more along the canal towpath. As they did so it was established that three shots had been fired, one each from McDowall, Hugh Chalmers and William Kelly, although none could confirm having hit anyone. As the smugglers gathered together once more, they discovered that William McFarlane and Duncan Graham had been wounded, while Graham’s brother George and McGregor were missing. Both men were found lying behind the wall where Duncan McFarlane had left McGregor. The former was able to walk but it was obvious Graham was seriously wounded. A contact named Ferguson lived nearby, so they obtained a large sheet from him and used it to carry Graham back to the house, where it became obvious that both he and William McFarlane required medical assistance. Around 6am that morning, several of the smugglers appeared at the Royal Infirmary, where the wounded men were examined by two surgeons, George McLeod and James Watson. Graham had died by this time, while McFarlane was in poor condition, having his left arm and leg amputated. McGregor was examined by a third surgeon, William Penman, who removed a pistol ball from his thigh.

Although the Glasgow Herald had reported the matter was under investigation, it is probable most considered there would be no further action. Therefore it was surprising to find Chalmers, Ingram, Gardner, McDowall and Kelly all standing in the dock at the High Court in Edinburgh on Monday 14th June. While in hospital, Duncan Graham and William McFarlane had made two ‘dying declarations,’ although subsequently they did recover. Both remained in hospital by the time that the trial began and the Solicitor General, Henry Home Drummond, who was leading the prosecution, intimated that he would not use the declarations as evidence. However, knowing the smugglers remained in capacitated, one of the defence advocates, John Clerk, insisted they should be included, as they contained admissions that the smugglers had started the fight. Thinking that the two men would be unable to attend for some time and it was probable they would retract their statements in the interim, Clerk declined Drummond’s offer to have the trial delayed. Unfortunately for Clerk, the trial judge, Lord Boyle, the Lord Justice Clerk, had learned the men would be fit within a few days, so refused to allow the declarations to be included as he understood the men would be able to testify in person.

Dick was the first witness, stating that one of the smugglers had laid down his flask slowly when challenged but, as he moved forward to retrieve it, he was struck by the cudgel and stunned. He had been armed with a stuff stick but claimed he had not drawn it and used it only to fend off further blows. As he recovered, he had become engaged with another smuggler and, as they struggled, saw McDowall pull back from the man he was attacking and fire his pistol. At this point, Dick felt McDowall was having the worst of the struggle but, following the shot, he saw the smuggler run off. Another of the excise officers, Alexander Mudie confirmed that the smuggler he had tackled had laid down his flask and initially stood quietly. Then, as Dick was struck, the man took the opportunity to flee and, according to the excise officer he was not involved further in the fight, although his colleagues were hard pressed at one point. Another excise officer, Buchanan, confirmed that all but Ingram had been armed with stuff sticks, referring to the Bishopbriggs incident among others where it was known smuggling gangs had been armed and prepared to resist.

Although the declarations admitted the men had been involved in smuggling, none of them had been charged with any offence following this incident. Five of them gave evidence, Duncan McFarlane, McAlpine, McGregor, Samuel Cameron and Robert McLaren. All of them told identical stories, claiming that they had laid down the flasks when demanded and, although armed, used the cudgels only to fend off the blows of the aggressive excise officers. As each of the smugglers repeated the same story they drew a sarcastic comment from the Judge. He could not consider it true that ‘eight Scotchmen (sic) with sticks in their hands, would remain for five or ten minutes to being cut and slashed at, without ever striking a blow.’ When McLaren was asked whether the excise men could have seized the whisky without being armed, the Solicitor General tried to object to the question. However the judge over-ruled him and the witness was forced to admit they could not.

After hearing evidence from the surgeons who treated the victims, plus depositions by the accused, the court rose for the day. The jury contemplated their verdict all of the following morning before declaring the case against the excise officers ‘Not Proven’ at 1pm. Later it was learned that this verdict had been reached only by one vote, seven of the jury considering them guilty of culpable homicide. Before releasing them, Lord Boyle told the officers he considered the verdict correct but he had some comments to make. They were fortunate to have escaped punishment, both for failing to identify themselves and from refraining to use minimal force. Therefore, he warned them to be more prudent in future when faced with similar situations.

Although there were no further incidents recorded in the Maryhill area, the whisky smuggling trade continued to prosper until 1822, when greater powers were given to excise officers, followed in the next year by the Excise Act, which revolutionised the trade. Due to this the bottom fell out of the smuggling trade and the introduction of the legitimate whisky industry that exists in Scotland today. There is no record of when the cairn was erected at the side of Maryhill Rd, or by whom, although probably it was a spontaneous gesture by supporters of the smugglers. In the same manner that people with little or no connection see the need to leave flowers etc. at the site of modern tragedies, it is probable that local people and travellers from the Aberfoyle area had similar motivation.

While throughout the 19th century most Maryhill people knew about the smuggler’s stone, it appears that the details of the story were lost quite quickly and imagination allowed to roam freely. In consequence the following poem was published, probably around 1905, although the publication is unknown, having been discovered in a scrapbook in the Mitchell Library :

The Ghost of Kelvinside

There’s many a story you’ve heard me tell

How this and that and the other befell

But never, I’ve told of the awful ride Of the terrible ghost of Kelvinside

It was late at night as slone I sat

In my room in a cosy first floor flat

While I puffed my pipe the fire burned low

With hollows of crimson and purple glow

All was silent, and never a light

From the neighbouring windows around shone bright

Save the street lamp’s glimmer, which showed the way

Shining and wet ‘neath its flickering ray

For a storm of sleet, like a spectre bride

Whirled round my dwelling in Kelvinside

At two o’ clock, neither less nor more#

Came a muffled knock on my outer door

Who could it be at the hour of two

None could I think of, no one I knew

Would call me up at an hour so late

Unless his trouble and need were great

But I went and listened, then open’d wide The door to the Ghost of Kelvinside

My nerves were alert, my arm was strong

And I thought to myself “My friend you’re wrong if you think you’ll stagger a man like me”

So silent I waited that I might see

How the visitor, tall and weird, would deal

With a fellow whose nerves were “true as steel”

But the visitor bore himself with pride

And entered my house in Kelvinside

“Stop! Stop!” I exclaimed and upraised my hand But the figure advanced and would not stand

I barr’d his coming, but through my arm

He strode in a way that caused alarm

Limp, to my side, fell the outstretched limb

And the sight of my eyes grew dazed and dim

The fall of his feet never rais’d a sound

As he flitted from room to room around

Appalled I followed, and cold dead air

Was wafted about me as here and there

He paused, in apparent fruitless quest

In ancient habiliments quaintly derest

He knelt near a closet with ear to floor

And, I thought I detected a distant roar

Of voices like troopers in hot pursuit

Of a fugitive flying. The Ghost knelt mute

But over his visage a dark scowl came

And his sunken eyeballs seem’d darting flame

Then he rush’d to and open’d a window wide

And leapt to the roadway in Kelvinside

A phantom charger, awaiting him, paw’d

The gravel outspread o’er the roadway broad

But never a sound from the stamp of hoof

Caus’d echo from window, or wall, or roof

The champing of bit and rattle of chin

Should have sounded clear thro’ the driving rain

But naught was heard, tho’ a neigh seem’d to come

From the throat of the steed – but the steed was dumb

A vault to the back of the prancing steed

And off went the rider at lightning speed

But never the clatter of hoof on stone

Gave an indication of flesh and bone

A tremulous trail of a glimmering blue

Was left by the rider as on he flew

At times they leapt, as if obstacle lay

At places where nothing now bars the way

Then a shot rang out, and the rider and horse Fell prone to the earth – the rider a corse

I crept to my couch and hoped I might sleep I long’d for oblivion, clam and deep

With head under blankets, I strove in vain

To banish the spectre and slumber again

At length, with the dawn of daylight, I slept

Exhausted, and slumber my tired eyes kept

Haggard, unshaven, and bloodshot of eye

Was my morning look, and I don’t deny

I was rallied and “chaffed” by friends, in joke

On my way to the town, but no word I spoke

To al old time servant at once I went

And asked her to tell what the phantom meant

She told me the story, she’d heard when young Of a smuggler bold – who expir’d unhung – Shot where the passage from Forth to the Clyde

Winds near the old Sheepmount on Kelvinside

By the Aberfoyle clachan, from north he hied

With spirits for skippers who sailed from the Clyde

This story I’d heard from her as a child Just clear of the manor of Kelvinside

And I know that his ghost still fitful frets

O’er scenes of his sins (which it ne’er forgets)

For never a prayer o’er his shallow grave

Was uttered to hope his spirit to save

You will find old people in Maryhill

Remember the smuggler story still

But only a few of the oldest tell

The legend my nurse remembers well

“Go visit his grave,” she said to me

“and say the word’sleep’ – say it three times three”

So I did as bidden, beneath a shed

Which covers the spot where the man fell dead

And I hope that when next abroad he may ride

He won’t “call” at my dwelling in Kelvinside

-MONK BRETTON-

The author of this essay is a retired training manager who carries out research into less well known areas of local history in Glasgow and the West of Scotland. As a Maryhill native he has a particular interest in the history of the area and, especially, that of the old police burgh up until 1891. These essays are taken from the research notes that have been drawn up over a period of years and are intended as an introduction which can be used by those seeking more information.

Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust want to thank William Black for his incredible support throughout the years, having shared all his in-depth research and snippets since the start of the Trust’s journey into the history of the Burgh. We are also very grateful for allowing us to post his wonderful essays to our blog.