Artist highlight: Hilda Goldwag

Words by Alyssa Mills

October (1962) via East Dumbartonshire Council

In a time of renewed focus on questions of culture and identity in Britain and Scotland, it is vital to recognise the outstanding contributions of immigrant and refugee artists, such as Hilda Goldwag. Looking at Goldwag’s charming, lived-in tenements or idyllic landscapes on the banks of the Clyde, it is clear with every brushstroke the love Goldwag had for her adoptive city. Goldwag takes a different approach to her contemporaries, neither highlighting the poverty and social unrest which accompanied Glasgow’s industrial decline nor neglecting its reality in favour of a glamourised portrait of the city.

Conversation via Clare Henry Art Journal

Having trained in painting as a young girl in Vienna, Goldwag was influenced by the less traditional compositions and colours being forwarded by European expressionists, especially the German-led Die Brücke style. While an increasingly abstract style was gaining prominence in British art, Norbert Lynton (1994) describes Die Brücke as uniquely bright in colour and ‘assertively primitive’ in form, with ‘at first sight no sign in their work of direct social comment or even of personal anxieties.’ Both Goldwag’s figures and landscapes feel nostalgic and honest - a realistic depiction of the world through the lens of someone who cares deeply about their subject. But to say Goldwag’s art is apolitical is inaccurate. Her comforting, domestic scenes are defiant in their affection, creating a theme through over 60 years of painting. Her work is intimate and optimistic, a lens through which the oft-dilapidated canals and streets of Glasgow are transformed into a vibrant cityscape which feels instantly familiar to those who love Glasgow like Hilda.

Early Life

Blinds via McTear’s

Hilda Goldwag was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1912, and trained as an artist against the backdrop of the growing Nazi regime. Only a year after graduating with a degree in graphic arts, Hilda had to leave her home and family for the safety of the UK, moving to Edinburgh and shortly later, Glasgow as a refugee. Her family, expected to follow six months later, were approved to travel the day WWII broke out, leaving them stranded in Austria. Goldwag’s mother, brother, sister, brother-in-law, and young nephew were eventually killed. This grief is recurrent in Goldwag’s work, as is the sudden isolation she experienced as the sole surviving member of her family, alone in an entirely new and unfamiliar country. Her painting Blinds evokes the unnerving mixture of fear and curiosity she must have been feeling in her early years living in the UK.

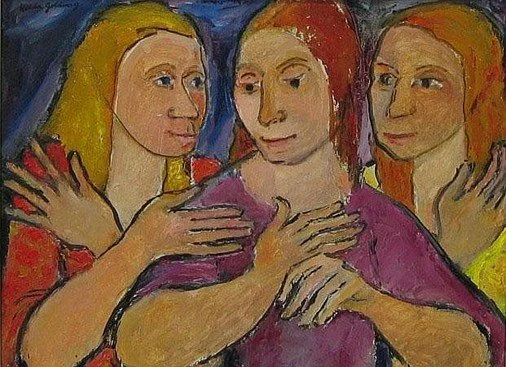

Despite not pursuing her art full-time until retirement, Goldwag quickly moved from domestic help for a Church of Scotland minister to Head of Design for a Glasgow printworks, primarily designing scarves for Marks and Spencer's and working as a freelance illustrator for children's books, cards, and magazine. She also enrolled in life drawing classes at the Glasgow School of Art in 1945. Perhaps her most widely distributed work is the original illustrations for Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses (1955) for Harper Collins.

Making A Life

Cecile Schwarzchild (left) and Hilda Goldwag (right) in the 1940s

via Scottish Jewish Archives Centre

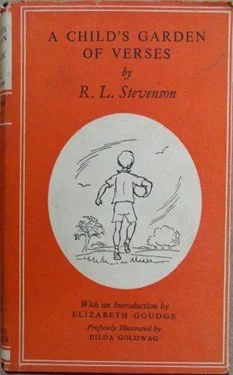

Cecile Schwarzschild (1915–1998) via Scottish Jewish Archives Centre

Mirror Image via McTear’s

Shortly after Hilda’s initial move to the UK, she met fellow refugee Cacilie Zoe Schwartzchild, or Cecile, in a Quaker meeting house in Edinburgh. The two became quick and enduring friends, and did war work alongside each other at McGlashan Engineering Works in Glasgow. The two remained close for decades until Cecile’s death in 1998. Even before she began painting full-time, Hilda painted her lifelong companion many times from life and from memory. The portrait above was painted shortly after Cecile’s death, depicting her young, as Hilda may have met her. Even where Cecile isn’t explicitly the subject of Goldwag’s art, the relationship between these two women lingers in her many figure paintings of couples - young and old; familial, platonic, and romantic - who appear to comfort each through a terrifying and uncertain post-war world. Both women were torn away from beloved family by the Holocaust and lived in a world defined by grief. The importance of this companionship to Goldwag’s life and work cannot be overstated. Hilda’s work in the years after Cecile’s death speak to an enduring loneliness which is echoed in the myriad forms of grief experienced by its audience

Depicting Glasgow

Artist Assessing Her Work 18-07-90 by David Holgate

While Hilda worked primarily in creative and design work post-war, she continued painting as a passion, usually using oil paints and a palette knife on board, as canvas was prohibitively expensive. From the 1950s until her death in 2008, Hilda would pile her supplies into a shopping cart and cross the city and especially Maryhill on city buses, leaving her completed paintings to dry on the luggage racks. She completed dozens of paintings in this period utilizing her distinct and evocative expressionist style to represent Glasgow’s crumbling tenements criss-crossed by washing lines, the declining industrial technology overtaken by the city’s great green places on the banks of the canal, and, with the same brush, the weary but determined people of Glasgow. While avoiding explicit or heavy-handed political imagery, Goldwag nonetheless leverages dynamic posing and framing, bold colours, and complex shape language to bring to life the everyday dichotomy a city that was post-war and post-industrial, and yet on the verge of a cultural revival. These domestic scenes are honest and familiar, such as Springtime Courting Scene, which is immediately familiar to the thousands of Glaswegians who visit its many parks every day for a picnic or to soak up brief rays of sunlight between rainstorms.

Springtime Courting Scene

via Glasgow Life

If one thing is clear to the viewer of Goldwag’s paintings, it's a deep and enduring love for her adoptive city. Her landscapes are broad in subject, depicting the Forth and Clyde Canal and the tenements and factories on its banks, flowers, farms, waterfalls, rivers, and more. In regard to Goldwag’s landscapes, artist Alexander Moffat claims 'her intimate glimpses of canal sides, snow covered streets, trees in blossom, suggest an optimistic view of urban life'.

Broken Fence via McTear’s

As a Glasgow transplant myself, the lens through which Hilda Goldwag depicts her home is intimately relatable. Her imagery is honest, never over-glorifying and neither highlighting the symptoms of industrial decline and poverty which is and was ever-present in the city. The crooked churches and winding canals are the heart of a city built by and for its workers, many of whom are, like Hilda, refugees and immigrants. Even where figures are absent from the painting, her landscapes are lived in. One example is Broken Fence, which depicts a fence twisted and rent by a violent storm. The composition and colour are dynamic, and the lighting is low enough to disorient the viewer before the image comes into focus. The painting is chaotic and disorienting, giving the viewer the feeling of being outside during a heavy storm, wind whipping about. These works are whimsical and heartfelt without leaning towards the absurd; and represents a very conflicted time for Glasgow’s identity with nuance and hope.

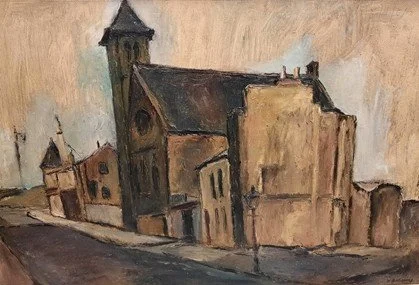

Church on Maitland Street via East Dunbartonshire Council

Dam Overspill on display in Maryhill Burgh Halls

With protests against immigrants and refugees taking place across the UK, it is more essential than ever to recognize that there are few who love and contribute to the UK more than its immigrants and refugees. The idea of ‘protecting British culture’, often invoked in debates about immigration and identity, too often overlooks the invaluable contributions of the many immigrant-led communities and subcultures that have shaped the nations. Artists, engineers, politicians, craftspeople, writers, and labourers across the country have contributed to the complex tapestry of the culture we live in. Hilda Goldwag gave up everything for a chance to build a life free from oppression, including, unfortunately, her family. Hilda Goldwag is one of few Glaswegian artists whose work primarily depicts the city itself, and more than that, Hilda herself is a part of the fabric of the city. By painting in situ, and in so many locations throughout the city, Goldwag’s process was as much art as her finished work, and her and her shopping cart loaded with paintings and supplies became a familiar sight to Glasgow’s residents. Looking through a collection of Goldwag’s paintings serves as sort of tour of the city, preserving a tumultuous period of its history in work that speaks to both to its reality and its underlying spirit.

In her lifetime, Hilda Goldwag received modest recognition but was never considered a renowned artist. She exhibited her work in Gourock, Greenock and at the Lillie Art Gallery in Milngavie; received awards from the Glasgow Society of Women Artists; and was a professional and exhibiting member of the Scottish Society of Women Artists, the Paisley Art Club and the Milngavie Art Club. It is impossible to question Hilda’s talent, but one must wonder her intention when creating art. Her style, which so tenderly depicts friends and strangers alongside tenements and canal scenes, each viewed through an eye which finds beauty because of, and not in spite of, its flaws, speaks to an artist who has found comfort and community amid impossible circumstances. In times like these, when the world seems to be falling apart, there is a quiet resilience in seeking out the beauty of our local space and working to make it better. Hilda Goldwag, and countless refugees and immigrants like her, have made essential contributions to the towns and cities they call home, and it is vital that their current and future place in Scottish culture is fiercely protected.

You can see Dam Overspill here in Maryhill Burgh Halls.

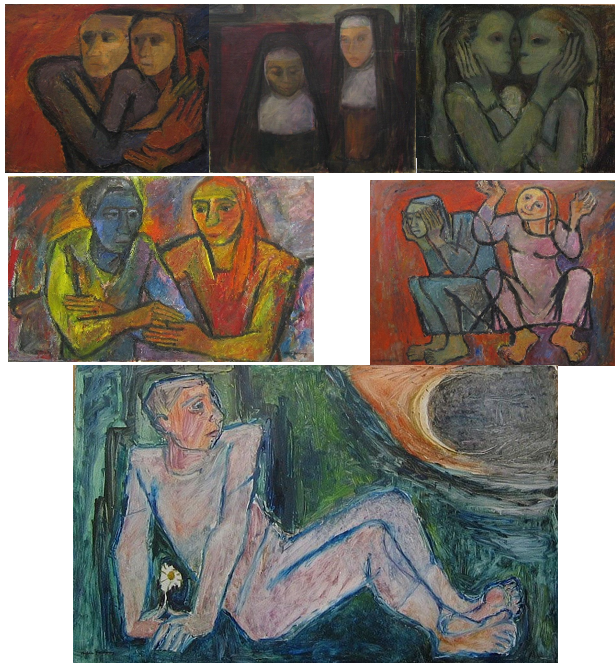

Explore some of the rest of Hilda’s work below, with paintings chosen to emphasise the breadth of style and subject which Hilda lent her considerable skill and unique perspective to bring to life. All paintings featured here are found at Invaluable Auctions site.

In order, paintings are as follows. Portrait Study of a Woman, Old Woman, Schoolgirl on the Beam, Shadow, Nightmare, Man Helping Man, Old Man with Daughter, Icy Crags, Ripple, Woman in Shades of Blue, Dance, Two Faces, Two Nuns, Twin Heads, Women, Contemplating the Moon, and The Guide.